In July of 1972, Curtis Mayfield’s soundtrack to the movie Superfly became a landmark in exposing the threat of drugs to the Black Community. A year after Marvin Gaye’s What’s Goin’ On, Mayfield’s songs on Superfly showed how the impact of heroin, cocaine, and the rampant abuse of other drugs resulted in significant deadly repercussions on Inner City residents.

Marc Myers of the Wall Street Journal recently wrote about this iconic album:

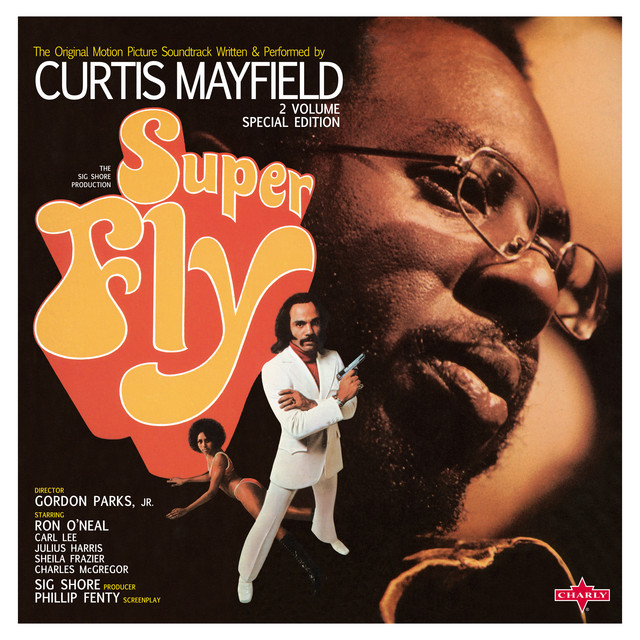

In December 1971, Curtis Mayfield was movin’ on up. After 10 years of writing and recording hits for the Impressions, such as “Keep on Pushing,” “People Get Ready” and “We’re a Winner,” the lead singer caught a big break. He was approached backstage after a solo concert at New York’s Philharmonic Hall by a screenwriter and film producer who invited him to write and record the soundtrack for a feature film called “Superfly.”

Jetting home to Chicago the next day, Mayfield leafed through the script about a Harlem drug dealer’s struggle to quit the business and sketched out several songs. But when Mayfield saw the film’s rushes a short time later, he recounted in Peter Burns’s 2003 biography, the movie had become a “cocaine infomercial.” Rather than quit, he wrote lyrics that exposed what the film ignored—the punishing impact of drugs on black inner-city neighborhoods and families.

When Mayfield’s “Superfly” soundtrack was released 50 years ago, in July 1972, a month before the film’s debut, the music was smarter and more sophisticated than the movie itself. The record spent four weeks at No. 1 on Billboard’s album chart, sold a half-million copies in two months and was inducted into the Grammy Hall of Fame in 1998, a year before Mayfield’s death. It also inspired soul albums to address the deterioration of black urban life. The record’s sales were remarkable given that “Superfly” played like a public-service ad. For the soundtrack, Mayfield had created a series of soft-funk hope songs designed to counter the movie’s glamorization of cocaine and the playboy lifestyle of dealers.

The album arrived at a pivotal moment in black music. It came out two years after Mayfield’s first solo album, “Curtis” (1970)—a socially conscious record that predated Marvin Gaye’s “What’s Going On” and Gil Scott-Heron’s “Pieces of a Man” (both 1971). In turn, “Superfly” set the tone for message albums by artists such as Stevie Wonder, Lou Bond and Sam Dees.

As for black film, the so-called blaxploitation genre had just emerged in Hollywood with the success of Melvin Van Peebles’s “Sweet Sweetback’s Baadasssss Song” and Gordon Parks’s “Shaft” in 1971. Both featured black leading actors and casts taking on police corruption and, in the case of “Shaft,” organized crime’s grip on black communities.

Growing up in Chicago, Mayfield had witnessed the corrosive effects of drug and alcohol addiction and thought “Superfly” required a fresh approach to lyric writing. “General statements [in songs] are all very well,” Mayfield told British journalist Roger St. Pierre in 1972, “but [if you] fit the statement into a personal context which the listener can place himself into, you have something with much more impact.”

Shot on location and directed by Gordon Parks Jr. , son of the “Shaft” director, “Superfly” provides a fascinating pigeon’s-eye view of a crumbling New York on the cusp of recession. While the film today sags under the weight of wooden acting, clichéd dialogue and stereotypes, Mayfield’s songs and cooing falsetto remain exceptional.

The record’s orchestral drama was created by Johnny Pate, a leading Chicago jazz-soul producer and arranger who had worked with Mayfield and the Impressions since 1963 and gave their hits and albums a brassy urgency.

“Superfly” opens with organ chords, a restless conga and wailing electric guitar on “Little Child Runnin’ Wild.” Mayfield’s lyrics address the demand side of the drug epidemic: “Broken home / Father gone / Mama tired / So he’s all alone . . . Don’t care what nobody say / I got to take the pain away / It’s getting worser day by day / And all my life has been this way.”

The supply side comes next on “Pusherman,” and features Joseph “Lucky” Scott’s funky electric bass line, which captures the dealer’s seductive personality: “Want some coke? Have some weed / You know me, I’m your friend / Your main boy, thick and thin / I’m your pusherman.”

Supply and demand collide on the third track, “Freddie’s Dead.” The hit song features a catchy bass riff with a flute on top, strings and fuzz guitar—all reminiscent of Isaac Hayes’s “Theme From Shaft”: “Everybody’s misused him / Ripped him up and abused him / Another junkie plan / Pushin’ dope for the man.”

“Eddie You Should Know Better” chastises the dealer’s partner, who doesn’t want to quit: “Must be something that’s freezin’ his mind / That has made him, through greed, so very blind / And I don’t think he’s gonna make it this time.”

Musically, “No Thing on Me (Cocaine Song)” is reminiscent of Gaye’s “Mercy Mercy Me”—a lush, upbeat recap, with the lead character finally free of dealing: “I’m so glad I’ve got my own / So glad that I can see / My life’s a natural high.”

The album ends with the track “Superfly,” which hammers home why a dealer is a predator, not a patron: “This cat of the slum / Had a mind, wasn’t dumb / But a weakness was shown / ’Cause his hustle was wrong.”

Despite its inability to eliminate the drug culture, “Superfly” is one of the finest expressions of social-realist messaging in a soul soundtrack. In the years that followed, the album became a model for dozens of blaxploitation film scores, yet none of them could top Mayfield’s sincerity, empathy or success.

—Mr. Myers is the author of “Rock Concert: An Oral History as Told by the Artists, Backstage Insiders and Fans Who Were There” (Grove Press).

I was very moved the first time I heard “Freddie’s Dead” on the radio in 1972. Curtis Mayfield’s music was ground-breaking for the early Seventies. But, 50 years later, we’re still battling the destruction drug abuse inflicts on our society. And more Freddies are dead. GRADE: A

TRACK LIST:

| Little Child Runnin’ Wild | 5:15 | ||

| Pusherman | 4:50 | ||

| Freddie’s Dead | 5:08 | ||

| Junkie Chase (Instrumental) | 1:52 | ||

| Give Me Your Love (Love Song) | 4:15 | ||

| Eddie You Should Know Better | 2:14 | ||

| No Thing On Me (Cocaine Song) | 4:52 | ||

| Think (Instrumental) | 3:44 | ||

| Superfly | 3:51 |

As Barbara Pym once said of one of James Baldwin’s books: “One feels fortunate to have not lived the life that would enable one to write a book like that.” White suburban listeners were not Mayfield’s target audience, but we can appreciate his music while acknowledging it doesn’t reflect our daily lives. However George—in your first sentence, you say Superfly pre-dates Marvin Gaye’s What’s Going On by two years. I must respectfully disagree: What’s Going On was released in early 1971.

Back to Mayfield, I like this album, especially the title track, but my favorite Mayfield song is Move On Up with its wonderful horns section and encouraging/uplifting lyrics.

Deb, you’re right about What’s Goin’ On. Somehow I confused 1971 with 1973. Barbara Pym knew the world James Baldwin wrote about was hellish. As a kid, I liked the Impressions’ “It’s All Right” and “People Get Ready” not realizing Curtis Mayfield wrote those songs and was part of the group.

Mayfield is definitely someone whose contributions are tough to overestimate.

Todd, Mayfield’s tragic accident was disastrous!

“Freddie’s Dead ” is a true classic. Mayfield and Jerry Butler had some classic hits with The Impressions, but his later stuff was more hard edged.

Jeff, Curtis Mayfield became more politically active and it came out in his later music.

I didn’t realize that he wrote Jan Bradley’s “Mama Didn’t Lie.”

Jeff, I was shocked to learn that Curtis Mayfield wrote “Gypsy Woman,” the Brian Hyland hit.